Replacing Indigenous Forest Patches in the Riparian Zone of the Upper uMngeni River

Re-establishing indigenous forest patches

“The promotion of indigenous deciduous trees for rehabilitation of clearing programmes may be important as there would be no transpiration during periods when water resources are limited”

“The total accumulated sap flow per year for the three individual A. mearnsii and E. grandis trees was 6548 and 7405 La respectively. In contrast, the indigenous species averaged 2934L a, clearly demonstrating the higher water use of the introduced species”

The above statements are just two statements extracted from the publication mentioned above. While one has to be careful not to extract just the information that proves a pre-conceived notion, having read the paper, I think these take-outs are a fair representation of the whole, albeit overly summarised. The paper displays graphs in which is demonstrated how the alien (evergreen) species have a continual high water demand during the year, whereas the deciduous indigenous species, with their winter dormancy, show a very low water demand in the dry winter months. The dry winter months are those in which the river experiences its lowest, or ‘base’ flows, and is also the time of highest irrigation demand along the river.

This additional seasonal understanding of matters goes a long way to fully comprehend the extent of the demonstrated hydrological benefits outlined in the report. This also serves in justifying the expense and difficulty of removing alien invasive species in catchments generally, but more particularly along immediate riparian zones. The applicability of this report to the projects of Upland River Conservation is leveraged even further by the fact that this two year study was done in the heart of our Upper uMngeni Super Catchment project area, on New Forest Farm.

Before having been alerted to this study, we had identified seven small areas where alien invasive species have been removed, and where we hope to establish small indigenous forest patches. There are no doubt other suitable sites as well, but these are the first seven that have been mapped.

This was prompted by the notion that having removed the tree canopy from the river banks, we may have caused a sudden warming. While the river banks were largely unshaded a hundred years ago the more recent slow ingress of the alien canopy may have mitigated slight global warming. With the sudden removal we may have caused the environment to “catch up” on that warming in a short space of time. This has made us mindful of re-establishing tall woody river bank vegetation to achieve a natural level of shading. This shading would comprise mainly tall grassland and some Nchishi , but in at least in some places it means re-forestation with indigenous species.

The sites have been carefully chosen based on observation of where forest patches do occur, and where they might have occurred before the severe alien wattle infestation, which might have displaced them. In several cases, lone indigenous trees were found left standing after the wattle had been felled. In all cases the sites are steep, south-facing slopes along the river or tributary course. These areas are cool, and remain moist enough that they tend not to burn in winter.

In fact, money has already been raised to re-establish one of the seven envisaged forest patches.

With advise from a local indigenous tree nursery, and armed with a species list from another scientific study in the same forest, we plan to first establish the forest precursor shrubs. Once these get going, they are likely to form a frost- free micro-climate and canopy in which the trees themselves have a better chance of surviving the critical first few years. Once that is achieved, we plan to plant the trees themselves. These will of course include evergreen indigenous species, in the interests of maintaining the natural biodiverse mix, so the hydrological benefits may not be as stark as those reported in our opening quotes. The initiative does however represent a return to what conditions may have been before the invasion of alien trees.

In the interim, erosion control and re-grassing has been a priority for the bulk of the cleared river bank areas. Much has been achieved, but there remains a lot to do, especially along the banks of the Furth stream. Re-grassing efforts, and any required erosion control will continue parallel to our reforestation ambitions. We are currently exploring innovative funding solutions for each of the remaining six sites.

We certainly believe that the distinct and easily identifiable outcome of a forest patch, visible on Google Earth from anywhere in the world, might have appeal to funders who would like to be able to see the fruits of their contribution. Added to that, these small forest patches are between 800 and 5000 square metres only, and are therefore not expensive to create.

The Dreamstream

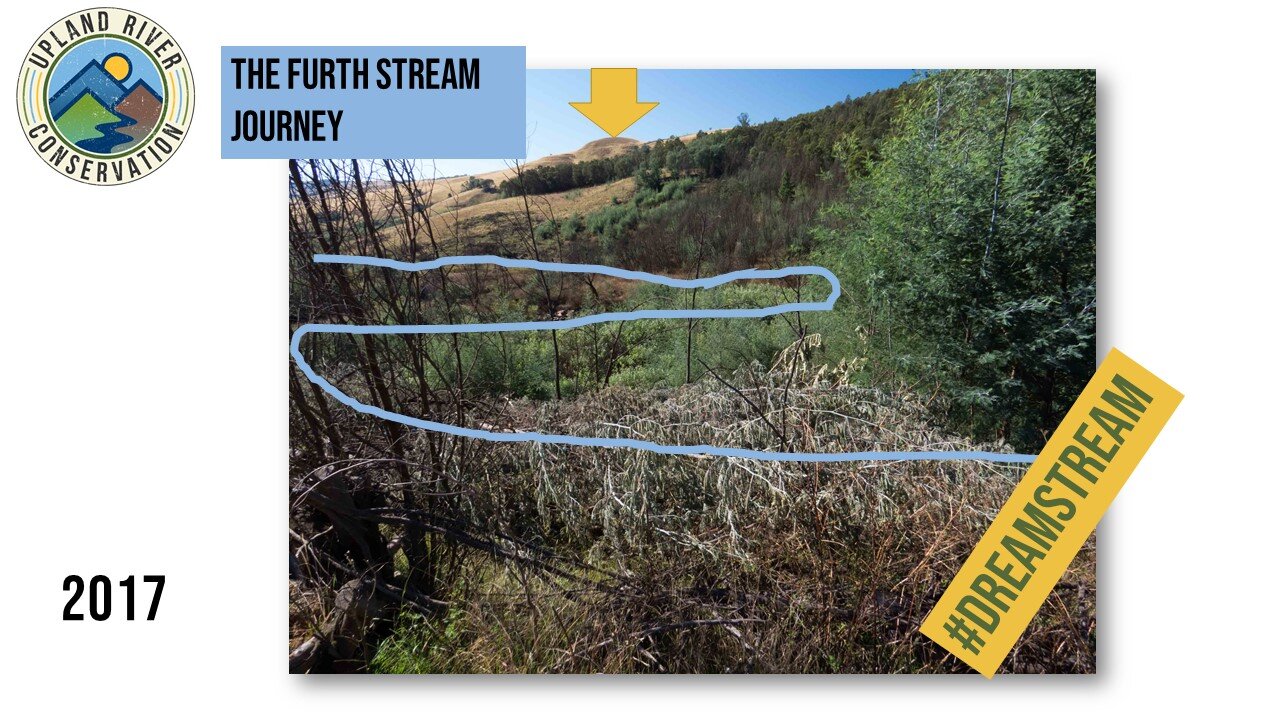

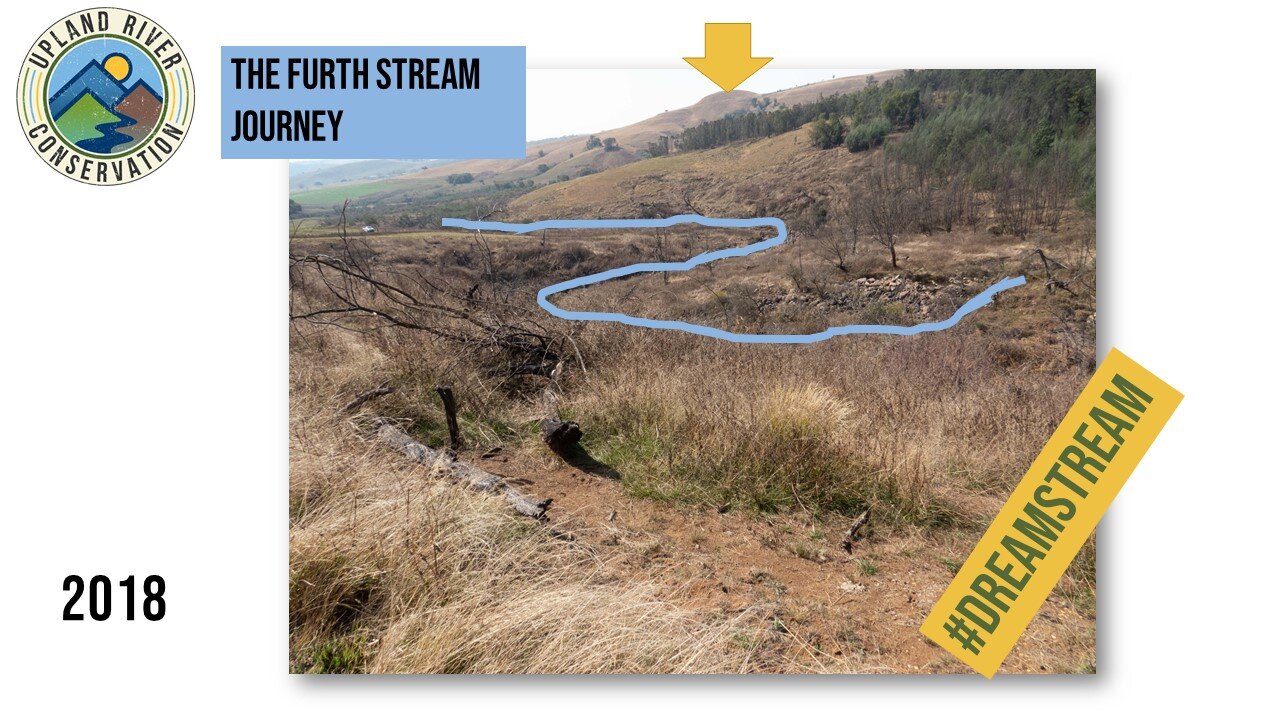

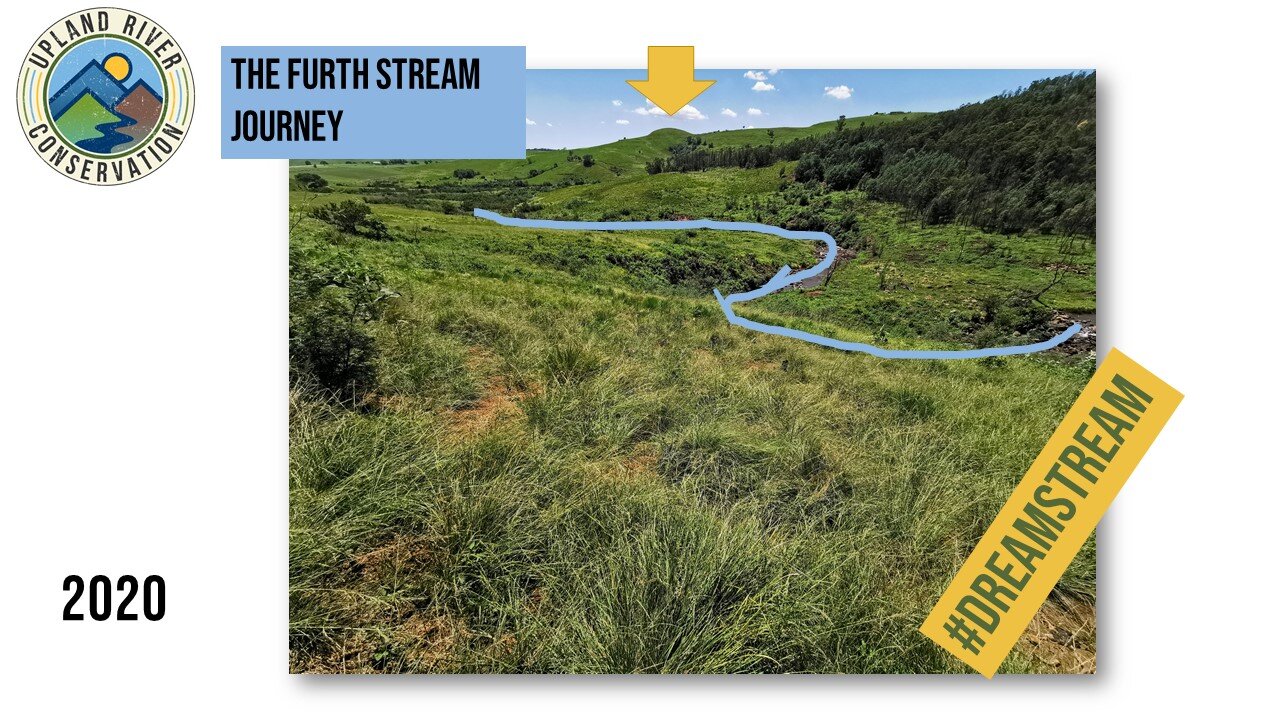

The Furth Stream is a good example of an area that was cleared of wattle, but which is in need of ongoing care and rehabilitation.

The Furth Stream is a tributary of the uMngeni River in the Dargle Valley in the KZN Midlands. This stream became inundated with black wattle trees in the approx last 5kms of its course, before its confluence with the uMngeni. Back in 2013/4, and stemming from a biodiversity stewardship program in the headwaters of the uMngeni, WWF arranged funding to clear the stream. That funding was part of an innovative Water Balance Program, in which industries downstream in the catchment were encouraged to become water neutral, by funding the removal of water-sapping trees in the catchment to the extent of their water use.

The stream was cleared of wattle initially, and then for 3 years thereafter, regrowth was controlled. After the 3 year period, the landowner is responsible for taking over the area, and keeping it clear of the invasive wattles.

In the case of the Furth Stream, the lower 4kms of the valley benefited from the input of the landowner’s lessor, namely the Natal Fly Fishers Club, who assisted the WWF in the day to day management of the contractor, and in the handover phase.

The devil lies in the detail of the hand-over to the landowner, and in the extent and nature of the follow-up measures required after the initial 4 year period. In several areas within the uMngeni catchment, the extent of the wattle regrowth, and the ability of grasslands to re-populate the cleared areas, have made for a successful formula.

The valley of the Furth stream is not one of them.

Here, difficult steep river valley territory has somehow contributed to rampant regrowth of wattle and other pioneer species. The amount of work required to control this, and to return the landscape to an economic grazing asset for the farmer, exceed the resources of the farmer, both in terms of cost, available time, and number of labourers to do the work.

Unlike some of the open hillsides that were cleared, the follow up work in the Furth Valley has been arduous. Between 2016 and 2019 the contractor passed through the valley twice each year, cutting and poisoning wattles and other plants. In 2019 the waste timber was removed from the immediate riparian zone, and in most years, fire passed through the valley. In witnessing this 3 year process, it was at times difficult to assess whether progress was in fact being made, or if the valley was going backwards.

In reviewing photographs and Google Earth images, it is clear that progress was in fact made, but even now, walking in the valley at times of rank re-growth, a layman would struggle to appreciate the amount of work that has been done, or to see the vision of what the valley should, and could ultimately look like.

In recent initiatives, post the handover to the landowner, minor (and sadly insufficient) clearing of regrowth has occurred, and erosion measures have been implemented by Upland River Conservation (URC) with help from the Duzi uMngeni Conservation Trust (DUCT) , The Natal Fly Fishers Club (NFFC) and the landowner. These measures have included planting of grass seed, and installation of erosion control mats, but are on a pilot scale only, due to the limit of resources.

At present the valley suffers from earth that was baked , and damaged, in fires that went through the valley and the piles of brush that lay there after the clearing work. The ground lies bare in many places, and in others is conducive to the germination of only wattle, bugweed, khakhi weed, bramble, and blackjacks. Grass cover of palatable species or otherwise, is currently very poor. The rank regrowth of combustible material, and the tendency of grass species to tolerate fire, act as incentives for the landowner to burn the area, and to the layman the burning practice achieves a “tidy up” which seems to have merit. However for a return to good basal cover, and soil structure, in which organic matter and mulch serve to speed the re-establishment of viable grassland, a more expensive management protocol is probably required.

Our objective is to continue to fell regrowth of alien pioneer species during the summer, so that a fire hazard does not accumulate ahead of the dry winter months. At the same time we seek to sow grass seed, which will benefit from the mulch effect of the cut weeds. So far, in our pilot areas, we have used a mix of seeds which includes fast germinating eragrostis teff, together with slower germinating indigenous species. e teff is indigenous to Ethiopia, but is a non-viable annual grass, so its purpose is merely to secure the soil, and out-compete weed seeds in the first season, while the slower-germinating species take hold. Once the slower species do take hold, it is intended that they too will compete with weed seeds by creating a cover through which the weeds are less likely to grow. Weeds growing within viable grazing species will also be controlled by grazing cattle. Once this carpet of dense cover is established, fire will again be an important part of the restoration formula. In addition to the above, old logs and erosion control mats will be used to stop sheet erosion where it occurs. The above is the protocol being implemented in the pilot areas.

The end result which we hope for, is a densely grassed valley, which has economic value to the farmer as grazing, and in which normal, and affordable agricultural practices of fire and grazing are adequate in preventing significant re-infestation by alien invasive plant species. Early indications are that we may have achieved this, at least to some degree, in the pilot area.

The Furth Stream work falls within URC’s “Upper uMngeni Super Catchment Project” proposal, which is currently seeking funding. In the meantime URC and the landowner will continue with what pilot work we are able to afford.

Treating floods and droughts with the same medicine

On a recent trip to the UK, I was alerted to the fact that the topic of soils is high on the agenda of environmentalists there. I was visiting various entities involved in river restoration, catchment sensitive farming, and the catchment based approach, and everywhere I went, the topic of soil health was on the lips of my hosts.

The reason for this, is that the UK has been hit by considerable flooding in recent years, and they are fast learning to replace measures such as mechanical dredging, with what they term NFM (Natural Flood Management). The concept is one in which you use the Ecological Infrastructure to protect you from floods instead of, or in support of the “grey infrastructure” (steel and concrete). So they build leaky dams, reconnect rivers with floodplains etc etc. But top of that list, and most widespread, was talk of improving soils, and more specifically their ability to hold onto water for longer, instead of letting go of it as fast as the rain falls upon it.

Now , with me having worded the sentence above as I have, it is probably dawning on you, as it did on me, how managing floods and managing drought, might have overlapping solutions. Keeping rainwater back in the catchment for longer, and stopping it from all rushing away at once, will minimise flood affects and drought affects. Here in SA, we have those 5 or so long dry months in winter, in which our rivers slow to a trickle. End of winter trickle is known as “base flow”. Just as the Poms want to keep water out of the coffee shops along the river Ouse in York, so we would like the rivers to flow stronger through August and September to support all the ecosystems that rely on those rivers (humans not excluded).

And having spongy deep soils that hold onto water achieves both.

The River Ouse in York

Site of considerable flooding

The uMngeni River in September

after long dry months

Studies show that soil with high organic matter levels and good structure, holds more water. In other words, a seldom burnt (not never) , never ploughed, piece of land in the berg, covered in thick natural grass, supplies us with more consistent river feed than a ploughed maize field where the trash is burnt every year.

These two are extremes….the berg and the maize field….. but more commonly the answer lies in subtleties of management in a vast area of grazed and burnt veld landscape. Farmers have the challenge of trying to maximise the tonnage of grass for their cows, while preserving a diversity of species, while keeping costs down and income up. Certain grazing and burning practices favour less palatable species. Other practices can result in poor basal cover (a lower number of plants per ha, which leaves bare ground between), and still more nuanced techniques give higher grass yield in wet years, or maybe in dry years, but probably not both. Farming neighbours are often dismissive of one another’s techniques. Fire regulations impose boundaries to what one can do, and every valley is different. Scientists from the varsity have vast research based knowledge. Farmers have vast local knowledge. National magazines can publish articles on best practice that are controversial, and not nationally applicable.

So what is best practice for drought and flood management?

The answer probably lies in area specific study groups, where scientists and farmers work together to establish their own unique best practice, for widest possible adoption in their own valley. The chances are, that despite the fact that we have farmed this land for over a hundred years, there will be some experimentation too.

Some reading matter on the topic:

What are the problems caused by wattle

Wattle trees are more problematic than you think. They don’t only sap valuable water….

The common and simple message about wattle, is that it sucks more water out of the catchment than indigenous vegetation. If that were the only problem with wattle, we would march out there and poison the lot and walk away. Until now several agencies have done just that. Doing that is a problem! It is an issue because in doing only that, one has not solved the problem at all. The need to understand the difficulties about wattle is therefore important when planning the removal of a wattle grove, including the timeline, resources and budget you may need.

Wattle does indeed sap a lot of water. I have heard figures of 1300 to 1600mm per annum. Rainfall in the area where we work is between 800 and 1200mm per annum.

Other important effects of wattle relate to the allelopathic effect, in which the plant prevents other species from growing in its leaf zone. I explore that on a real site outdoors in this video here:

Apart from how much water they draw, consider these aspects: Andrew takes us through a grove of wattle trees and shows real examples of the harm that they can do.

Another aspect to consider, is that wattle seed remains viable (i.e. they can germinate) for a whopping 60 years after they land on the ground! Wattle seeds are also triggered to germinate by fire.

As a legume, wattle puts some nitrogen into the soil. In addition, it causes the wash away of topsoil. Take a look at this explanatory video: wattle problems explained It also acidifies the soil. If you add all these factors together, it means that a patch of felled wattle will only be suitable habitat to a particular suite of species. Those species are pioneer species, and most are alien and themselves invasive. This is very evident in the field. One cannot wish grassland back! It is really hard work, and no one has nailed the formula of what to do, when the patch becomes a jungle of blackjack, wattle saplings, khaki bos, and bug weed. It is certainly easier if you patch is on flat land, accessible by tractor, and if the area has been de-stumped. I say this because continual mowing works really well in getting grasses back in there. But in the steep and sometimes remote valleys, this is not possible.

This business of wattle removal is therefore maturing into a more holistic field of “grassland re-establishment”, of which the initial felling, and even the first year or two of follow up, are very clearly just the beginning.

From a paper by Yapi, O’Farrell, Dziba and Esler, we learn:

“ active restoration is required to enhance ecosystem recovery (Beater et al. 2008; Gaertner et al. 2011; Le Maitre et al. 2011). In some cases, elevated levels of soil nutrients (Yelenik et al. 2007; Gaertner et al. 2011; Witkowski 2012) derived from nutrient rich litter, and N fixation in the case of legumes, can lead to the undesirable situation of reinvasion by the same and or other species after clearing”

So in summary, wattle causes erosion and sucks water, and its other, and equally significant problems manifest when you cut it down.

Further reading:

Re establishing grassland

What to do after the wattle is gone…

Re establishing grassland

Its not easy!

Re-establishing grassland is not easy! After removal of wattle, one inevitably ends up with bare earth, somewhat rich in nitrogen from the legume effect of wattle, arguably still affected by Wattle’s allelopathic effect, and littered with woody debris. Going from this to dense grassland does not happen easily. In fact, it could be argued that this step is more difficult than the task of removing the trees themselves.

For one thing a fire may have gone through the landscape. This could be a natural occurrence, or a move by the landowner to “tidy up”. Burning is also not necessarily wrong. In fact one school of thought is to burn regularly, so as to trigger germination of the huge bank of wattle seed, as a means of ‘flushing it out’. There is real merit in this. But if the trash has been piled high, the fire will have been damagingly hot, and the earth will be baked and laid bare. The pulverised, baked earth is often best described as orange talcum powder. It has no structure, is hydrophobic, and nothing will grow in it. It represents a real erosion hazard!

Quite aside from burn areas, the ground is receptive to pioneer species, most of which are alien. Blackjacks (bidens pilosa), Khakhi bos, and other tall species grow. They have a poor basal cover, but are better than bare earth. The challenge is to get desirable species in before those weeds can predominate and shade out the species we would like to see. By all accounts, seeding a mix representative of highland sourveld is something that has never succeeded. Locally, a “summer veld mix” can be bought, and although it is not fully representative of the highland species mix, it comes as close as one can get. Initially we preferred a mix of Lovegrass and Teff (Eragrostis curvula and Eragrostis teff). Teff is indigenous to Ethiopia, but it is an annual and does not re-seed. Its advantage is that it germinates quickly to hold the soil, and will attract cattle, bearing other species in their dung. The curvula takes longer to germinate but does come away well in the end. The problem is that the teff does not germinate if merely scattered on the site: it must be raked in. It also will not germinate if there is a dry hot spell of weather. Also, the curvula tends to dominate and not allow the natural ingress of a diversity of species. So we use the “summer Veld Mix”, and we seem to be having success.

This quote from Grassland habitat restoration by Smith, Diaz and Winder , sums it up well:

“We conclude that there is no “quick fix” for the establishment of a grassland community; long-term monitoring provides useful information on the trajectory of community development; sowing gets you something ,but it may not be the target vegetation you want that is difficult to establish and regenerate; it is important to sow a diverse mix as subsequent recruitment opportunities are probably limited; post-establishment management should be explored further and carefully considered as part of a restoration project.”

and from Farmers Weekly:

“Effective restoration of encroached areas is not a short-term project, but a long-term commitment. “Chopping down a few trees and using a bit of poison here and there won’t solve the problem. There’s no quick-fix – you need a management plan as well as a budget if you want to succeed,” says Arnaud. “But,” he adds, “the rewards pay off as the land becomes more productive and animals can flourish.”

Our best summary of the way to do it, will follow in further posts…….