A Recce to the Poort Stream valley

A drone recce up the Poort Stream valley taking a look at some past gains, plus planning where we will work next.

The Upper uMngeni Land Rehabilitation project

A wrap on our recent land rehabilitation project in the upper uMngeni catchment.

This program was run in collaboration with DUCT (The Duzi uMngeni Conservation Trust), and was funded by the Caterpillar Foundation from the USA.

The project was conceived by Upland River Conservation, and represented a pilot, in which we tested a model of co-funding, where landowners contributed to the cost of rehabilitating scrub timber land, through a cash contribution, as well as reliquishing the value of that scrub timber. The concept was born on the back of good beef prices at the time of application, and in light of wavering efforts by Working For Water , and the beginnings of greater policing by DFFE on unlicensed timber.

The idea was that a farmer would relinquish the value of scrub timber (which traditional timber contractors didn’t want to touch anyway), and that he would pay in an amount in order that he would come away with more grazing.

The work was to be done by strongly mentored local contractors, who would undergo a purpose-built training exercise, based on working on farms in the KZN Midlands, performing alien tree removal and other farm services.

So many farmers have said “I would outsource this work , if only I could find a decent contractor”, and we aimed to match that to a number of local, struggling contractors who hadn’t previously managed to rise to the occassion of filling that gap.

The program was a significant success overall. This statement takes into consideration that the targeted number of acres of dense scrub timber conversion to grassland was only 60% met, but that this was supplemented by the addition of another 253 acres of sparse alien tree removal, which saw us reach 86% of the targeted annual water savings. The success is also stated in view of the significant training and upliftment of local contractors, but even more so, the lessons learned that will guide future projects.

It had been our intention to achieve the 222 acres of dense alien invasive tree areas rehabilitated to grassland, but economic factors hampered efforts. The factors included a fall in the price of beef, and high timber prices, coupled with poor economic conditions, and it prompted farmers to fell timber for their own account and not invest in the land rehabilitation, or not to act at all. The addition of extra grazing was simply unattractive given the poor beef prices, in a wet year in which grazing was already plentiful. The good timber prices prompted farmers and traditional timber contractors to view scrub timber as a valuable resource, which they had not done before. We also struggled to find secure or reliable non-traditional markets for the biomass. In this way harvesters of traditional pulp timber, who did not lock the owner into a concomitant spend on grassland rehabilitation, out-competed our value proposition, in that they allowed farmers to put cash in their pockets, rather than spend money on adding grazing.

In hindsight, the responsibility of project sales to farmers falling on the shoulders of one individual also may have hampered our ability to achieve the full acreage. This is also relevant in that we encountered a great number of landowners who were ill-informed as to the harmful affects of the alien invasive trees on water resources, the perilous state of water resources in the catchment, or the legal requirements to eradicate unlicensed woodlots. The sales effort therefore required considerable background education, and was by its very nature slower than expected, as farmers (and more so, smallholders) needed time to understand and digest what we had assumed were compelling reasons to rehabilitate scrub timber land.

From a seasonal point of view, efforts were hampered in the first summer, by the highest rainfall on record, making farm tracks impassable, and conditions unworkable.

With the training of contractors, we quickly abandoned the recruitment of purveyors of professional training, having found that their material and context was often far removed from the realities of a rural contractor working in a commercial farming economy. Course material was therefore purpose built and delivered. Notwithstanding this, we did experience that the ability of contractors to implement what was learned in a lecture setting was disappointing. Furthermore the propensity of contractors to delegate work, leave their work sites and attend training during a working week proved difficult. We also came to understand that many contractors attended training only because of the prospect of attaining paying work, and that they quickly abandoned hope of being given paying work, and thus stopped attending training. For those who did attend a high percentage of the lecture-based training, the value of mentoring those at work as a means of cementing classroom knowledge, was quickly comprehended.

On the positive side, we did secure work with four farmers who were engaged and willing and in so doing we achieved 144 acres of fully remediated landscape, with erosion control and planting of dense grasses, exactly as envisioned. We also had no fewer that 25 contractors sign up with the program, all of whom gained at least some beneficial knowledge, 9 of whom obtained work, and 5 of whom achieved official endorsement in the community. The employment created put some 65 otherwise unemployed people to work for a time.

Furthermore the extension of the program into a second season by the Caterpillar Foundation, together with the identification of eligible sparse timber areas, prompted us to label a new parcel of work as F.A.R.M. (Furthering Arterial Rehab and Maintenance)and continue with the budget. With this component we essentially filled the gap left by Working for Water in recent years, and we attended to road verges and river/stream banks, which allowed us to achieve considerable water savings, offer mentored employment, and further our credibility amongst the landowners.

This second phase of work was conceptualised in a way that allowed us to further our alien invasive tree eradication, and associated water savings, without being seen to abandon or back-track on our original co-funding formula. We felt it remains important to introduce subsidised land rehabilitation, rather than capitulate into performing work for free. Our objective of weaning both our contractors and landowners off low quality, low benefit alien invasive tree eradication remains in tact, and this project has served to bring into focus the challenges and their potential solutions.

We have learned that any such projects in the future should be preceded by a basket of landowner information initiatives, in which the legal and environmental costs of allowing unlicensed alien invasive tree infestations to endure, are brought into focus. We also learned that such interventions would need to vary in nature to effectively reach two distinct markets, namely commercial farmers, and smallholders, whose profiles and value-drivers are distinctly different.

From the perspective of the training of contractors, we learned that there is a dearth of suitable training materials and solutions for this type of contractor training in a rural agricultural setting. The training content had to be developed specifically for this program but is not wasted as it will serve future projects very well. In particular we developed a pricing method (on paper as well as on MS Excel) , which enables contractors to enter the land area, or man days, and distance from their base, and quickly arrive at a well considered price, with decent, respectable margins. We also came to appreciate that the training needs to be more heavily supplemented with on-the-job mentoring, with real-life examples on work sites brought to the fore as learning opportunities.

We are grateful to our partners (DUCT), and the Caterpillar Foundation for making this project happen. We are also grateful to the gracious landowners and occupants of the upper uMngeni catchment, for listening, understanding, and working alongside us for a better environment.

Would you like to be a catchment partner?

Join hands with other small businesses in your own catchment to enable a practical initiative that benefits communities, rivers and your own security of water supply.

We are seeking more local, small business sponsors to participate in this very local, very tangible and simple initiative. This simple model is the springboard from which we can unlock all manner of projects and co-funding, to perform actions along river banks in the communities of the headwaters. Targeting areas like the remote Lotheni , uMkhomazi and Inzinga rivers (for example) , we can establish links , and then work towards sustainable solutions that find small business opportunities that benefit the environment and inhabitants alike.

This is not aimed at the huge corporates with large CSI budgets that are fiercely contested, and which demand the high overheads of glossy reporting for boards of directors.

This is a small, practical, and bang-for-buck initiative, for any local businesses that use any water at all, to get involved in their own catchment.

R50,000 spread over 3 years, gets your business into a significant and meaningful endeavor which you can showcase to your customers, suppliers and staff. This opens the door to other sponsors with more money, allowing you to leverage a small investment towards tangible water benefits for when El Nino hits us next year.

Going where others don’t

A wrap up of a highly successful project on the upper uMngeni River

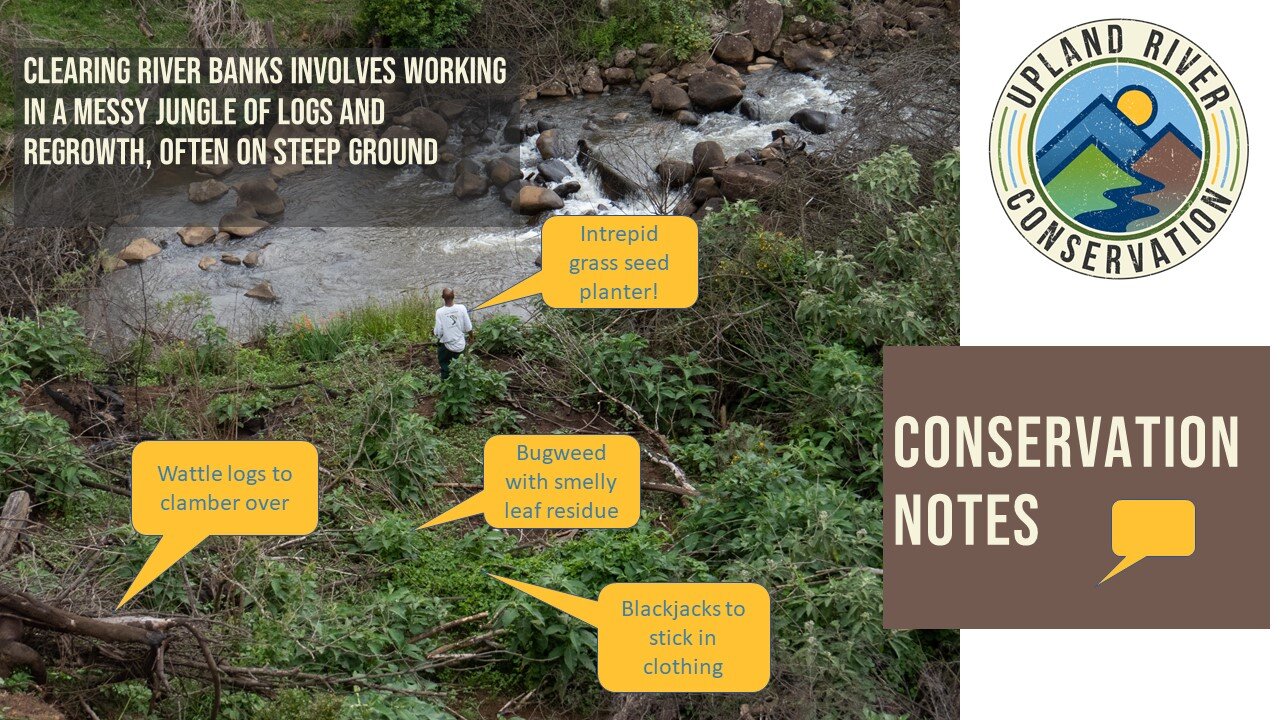

Between October 2021 and December 2022, Upland River Conservation undertook a project along the upper uMngeni and its tributaries to clear inaccessible areas. The areas in question were variously steep, or remote, or in some way difficult to reach. Since projects are difficult to supervise and manage in these spots, they are apt to get bypassed by other agencies.

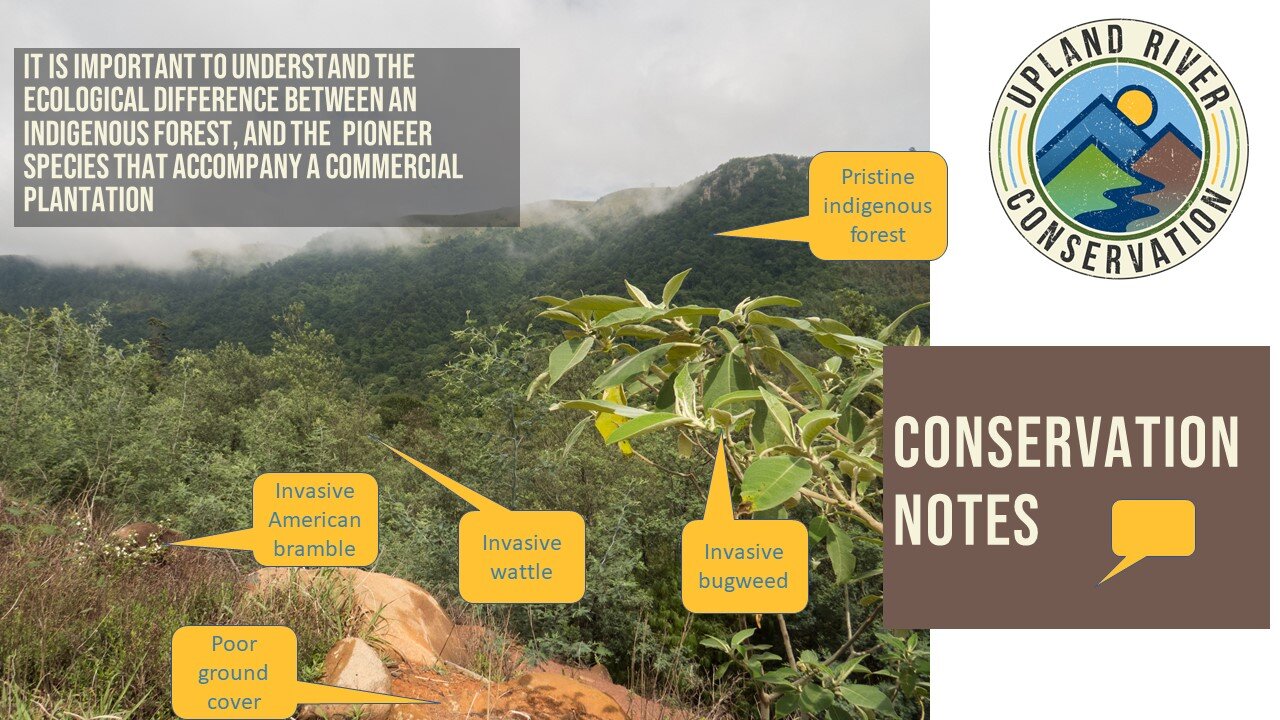

This was all the more evident, since NRM (“Working for water”) and other teams worked through the catchment in 2021 and 2022, and the areas which they skipped (often with good reason), were the ones we targeted.

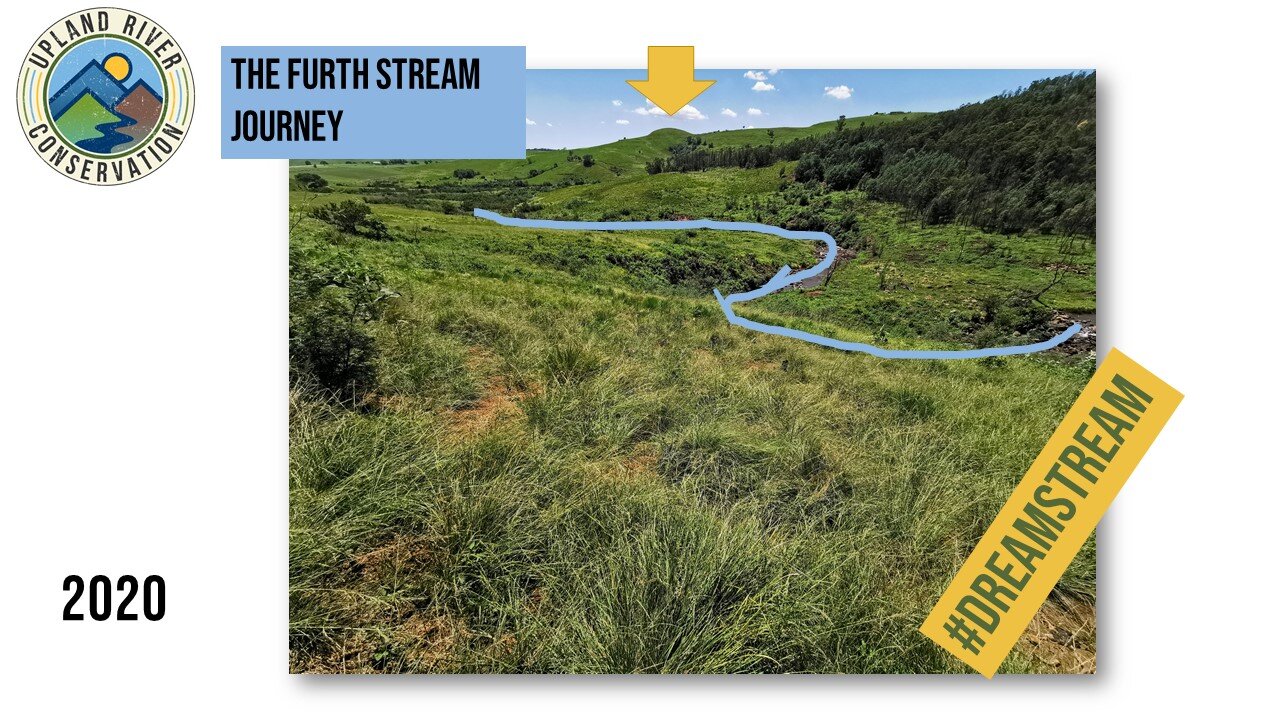

One site (tackled in Oct/Nov/Dec 2021) was on the Furth Stream (an uMngeni tributary). Here we cleared wattle, treated stumps with herbicide, and planted grass, on what were largely north and east facing slopes. The planting of grass was a significant aspect of this project. The idea is to at least partially out-compete wattle re-growth. More importantly, we want to attract the farmer’s beef cattle into the areas. Cattle, with their big un-selective mouths, will do our follow-up work for us by ingesting tiny wattle saplings, but they will only do this if there is dense, nutritious grass to be had. So our aim was to rid the valley of wattle (at least in the riparian zone to start with), and get good grass growing. The area was seeded with a summer veld mix in the spring.

Work in progress on the Furth Stream

Timing is everything with this work. Grass is best established if sown in the spring (before Christmas). So we only got as far as completing this site in 2021, and then we had to wait until spring 2022 to start on the next sites. But before we leave the Furth site, take a look at the “after” picture taken 12 months later:

Only grassland and indigenous bush left

Fast forward to late July of 2022, when we were able to get going again, with the impending spring in mind. Our second site was in the deep gorge of the Poort valley. This site really is remote and difficult to reach, and clearing it of wattle was an enormous task. Our team did well, and as spring approached the broad swathe of cleared alien trees started to stand out.

The Poort gorge

Once we were done at the gorge, we commenced in October 2022 with a high altitude team. In this part of the project we tackled some 26 small cliffs along the river, where other agencies had not been able to clear due to the skills and equipment required to do this work. Mindful of the fact that a high altitude team doesn’t come cheap, and that cows can’t graze these areas, great care was taken to remove every last sapling of wattle, no matter how small, and to plant replacement vegetation. Given that grass seed couldn’t always be sprinkled, we used “plant pucks” (or “biscuits” as they came to be known by our climbers). These are small coffee-puck sized disks of compressed coco husk, into which we inserted grass seed. The biscuits were wedged into crevices or buried in small gaps along the cliffs, where they would await the first spring rains. Once wet, the biscuits swell, and retain moistuire, providing the seeds with a perfect germination place. On these sites, we also planted indigenous forest pioneer trees and shrubs on the south facing slopes.

By close of the project in December of 2022, we were well pleased with the result. Thanks to the work of various agencies clearing wattle in the last two years, topped off by this project in hard-to-reach places, this valley is now a sweep of grassland as it should be.

Thanks for this work must go to WWF South Africa, and the funder, PepsiCo. Without their co-ordinating and funding roles respectively, this work would not have been possible. Thank you to the teams of Joe Gwamanda, Jabulani Mthalani, Alfred Zuma, Wellington Mabaso, Henry Nene , and Nirvana Ramsaram. Thank you also for the input of Ivanhoe Farm in drone spraying wattle saplings we could not reach in the Poort gorge. Also to the Dargle Conservancy and Amanzi Ethu Nobuntu for allowing us to hire their sponsored team when our budget was running lean.

This truly was a team effort.

Ten years on

Ten years ago, Penny Rees and colleagues undertook a much publicized walk from the source of the uMngeni to the sea. They performed water sampling along the way, and wrote blog pots describing what they saw and the people they met along the way. It was a great piece of awareness building.

Ironically, I was not aware of the river walk at the time, and only became aware of it later. Thanks to the well recorded event on a blog site, that didn’t really matter….I was able to read about it later.

A year or so after the walk, the UEIP (uMngeni Ecological Infrastructure Partnership) was formed. Again, at the time, I was unaware of its formation. But in a weird twist of fate, the day of the first signatures to that partnership, I was part of a social gathering of flyfishers in Maritzburg, where we held a lucky draw to raise funds for environmental work on the uMngeni.

Ten years down the line:

· The Natal Fly Fishers Club raised over R350,000 to its “Roy Ward Fund” and spent most of it clearing wattle and re-grassing about 12kms of upper uMngeni river banks.

· I formed Upland River Conservation and made the care of the upper uMngeni and other rivers my full time vocation.

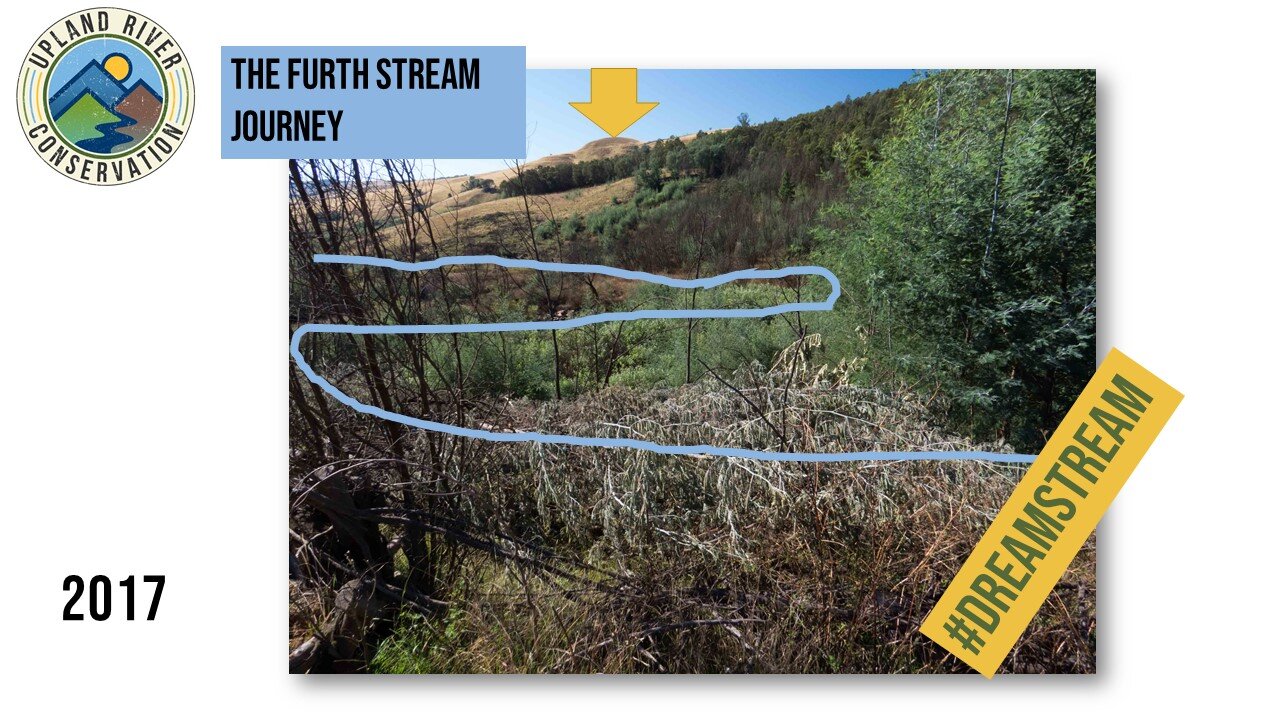

· The Furth Stream has been cleared, re-cleared, and cleared again. This year it has received grass seeding in a hope to stem the tide of wattle.

· Other uMngeni reaches and tributaries have been cleared by us at Upland River Conservation: either privately funded by landowners, or with grants and donations.

· The UEIP has had a lot of meetings and done a lot of strategizing and co-ordination. UEIP is in the process of forming a project co-ordination arm: a non-profit company called “Amanzi Ethu Nobuntu”.

· Pre-formation, DUCT has adopted a project for Amanzi Ethu Nobuntu…the DSI Enviro Champs project. In fact, it adopted the first project, which employed 300 people doing environmental work for 3 months, and now it is in the second project with 650 people working over 8 months. Some of these Enviro Champs are being hosted by the Dargle Conservancy, and within that the team is being deployed with sponsorship by the Natal Fly Fishers club to maintain its 12 + kms.

· Working for Water (now known as NRM) has been stalled due to all manner of government inefficiencies, but is set to re-start shortly and we will be directing their teams to carefully selected sites on the upper uMngeni.

· Pepsico, working though WWF and ourselves has funded a project to clear steep and inaccessible spots along the upper uMngeni…work started in the spring, is currently on hold due to the season, and will commence again this spring.

· Several projects have been proposed and grants applied for. Many have been declined. Two are looking hopeful.

But through all this, there remains an eclectic mix of situations. Millions of people remain unaware of the peril that the uMngeni catchment is in, despite Penny and her colleagues wonderful endeavour. The situation is all the more masked by the current exceptionally wet season. Most people I speak to are unaware of the approval of the Smithfield dam, the fact that it represents yet another hard infrastructure development while the more financially viable green infrastructure remains under-funded, and under-focused.

I think the upper parts of the uMngeni where I am focused are generally looking better. Many private landowners are playing their part, and working hard to remove alien plants. Some still plough up and down hills, plough up virgin veld without authorization, dig bare firebreaks down steep hills, drain wetlands and allow their slurry dams to overflow.

I personally spend a lot more time worrying about the river, and coming up with schemes and plans to make it better. I have to acknowledge though, that I spend too much time writing proposals, and attending meetings, and too little time out on the river with a saw in my hand and grass seed in my pocket, like I did when this was entirely a volunteer, after-hours endeavour. I am very mindful of this. There is a lot of report writing going on out there, and it swallows a LOT of money. I am resisting hard.

I have made up a mini SASS kit and gone out and done sampling along the upper river, and uploaded the results alongside Penny’s 2012 readings. I found stoneflies. On Friday I was out on a tributary checking on a contractor. He had skipped a few saplings. I have a saw under the seat of my bakkie. I got to work. I remain committed to bucking the trend; not being sucked into report writing; not becoming that office guy; keeping the actual work in the landscape central to what I do..

What I have written is another book. It will be out later this year. The proceeds will be going to the Natal Fly Fishers Club’s river restoration fund (The Roy Ward Fund).

We soldier on.

Andrew Fowler

Director

Upland River Conservation

Chestnuts Farm

In the week started 1 June 2021, we deployed a team under the leadership of Joe Gwamanda to work on the uMngeni River. Joe and his team are clearing both banks of the river from the Dargle Falls to the top boundary of Chestnuts Farm, a distance nearing 4 km.

The task involves felling and dragging out of the river, all alien invasive trees (Gums, Wattles, and Bugweed) of a size that can be dragged out by hand. Bigger ones will either be ring barked, or we will take up the offer of various landowners to pull them out with a tractor, in which case we will fell them.

The work involves wet feet, and we applaud Joe’s committed team, who were wading in a swollen river the day after it snowed, to pull out branches!

Wattles are consumers of large amounts of water, even more so when they grow directly on the river bank. It is territory that they favour, and the regrowth on the banks is considerable in places. This stretch was previously attended to by “Working for water”, but their modus operandi involves leaving trees in the river, and the river is still clogged with these logs many years later. Our work is slower and more expensive, but all logs are removed.

The funding for this project comes from previous fundraising efforts conducted by us together with DUCT.

We are thankful to the Addison, Griffin, Owen and Roche families for access to their properties and willingness to work alongside us and keep things tidy in years to come.

Volunteer Day

Calling on volunteers to come help a climbing team on the upper uMngeni River in the Dargle area.

Across the pond in the UK, volunteer days in villages seem to catch the imagination of the citizenry. Put up a poster in the local, and the next Saturday they seem to have people flocking to help tidy up the town or the stream, or the park. Our colleagues at Adopt-A-River have a monthly beach clean-up right here in KZN, and that seems to go well. It does perhaps help that the location is in a big city, from which it must be a bit easier to get a group of volunteers. In the highlands, the sites needing help are out in the countryside, and a volunteer has to travel there….in so doing, displaying a new level of commitment.

Nothwithstanding these fears, we have organised a volunteer day on the uMngeni River on Saturday 12th June 2021. The task at hand is to clear small sapling growth (wattles) off a very steep slope, on Brigadoon Farm on the uMngeni. This small cliff (about 15 metres high and around 200 metres long) was cleared of big trees in 2018. That task was completed by a specialist tree feller, with guys roping in with chainsaws. Of course the big trees are gone now, so it doesn’t make sense to pay a tree feller (upwards of R12,000 per day!) to cut small saplings.

In the last 2 years, follow up teams have cut saplings away either side of this cliff, but for safety reasons have avoided the slope itself.

Enter the Pine Busters!

Pine Busters are a fantastic group of volunteers who remove pines from hard-to-reach places in the Drakensberg. The thing they have in common is a love for mountain climbing, and they put these skills to work removing trees while hanging on ropes. While our site in the Dargle is tame compared to the cliffs they encounter in the berg, their skills are exactly what we need to get the job done.

They have offered to help us, and we are in return collecting a donation to help them out.

Volunteers to drag away the cut saplings, help fetch and carry gear, and maybe just get them a hot cup of coffee, are invited to join us for the day, or part thereof. We don’t mind if people come along to educate their kids, and all they do is re-fuel a chainsaw or go fetch a rope from the bakkie, we just need some hands on deck to make things go more smoothly.

So here is the invitation to you:

We meet at Taste Buds Farmstall at 8:30 am. Get there a few minutes and Sue or Nicky at Taste Buds will sell you a hot coffee and something delicious to eat. Then we leave any extra/unneeded cars behind and drive up to the farm (16kms) . Once there, we can leave low clearance cars near the dairy, and pile on any bakkies in the mix, and drive through the farm (2kms) to the site, which is right next to the farm road.

Anyone wanting to join for just a few hours, or anything up to the whole day, is most welcome to come along. The site is not dangerous, so we encourage you to bring your family and kids along. When you are there you can see what work has already been done on the river, and enjoy the spectacular views.

If you have any questions, please call or whatsapp Andrew on 082 57 44 262.

REPORT BACK:

Our small band of committed volunteers got a great job done. Most of the slope was cleared. A special thank-you to the members of “Pine Busters” who made it happen.

And as seen 5 months later in November 2021

A Champion

Hlengiwe Zuma of Impendle is an environmental hero.

Hlengiwe Zuma is a champion. This young lady is a government employee, working for DEFF, and seconded to the Impendle Municipality. In late 2020 she took it upon herself to arrange a wetlands information day for residents of the KwaNovuka village, which overlooks a precious wetland.

The wetland in question is part of the source of the uMngeni River. Ms Zuma understands the value of a precious and vulnerable water source, so, with no budget allocated to her at all, she did what was in her heart, and set about arranging this day.

Something like 200 attendees had access to various stalls erected by participating NGO’s, and just before lunch, we were treated to a short walk to the edge of the wetland, where the ecology and biodiversity and value was explained.

From left to right: Kholosa Magudu from Groundtruth, Nduduzo Khoza (crane expert) and Mlu Ntuli from Liberty NPO, after addressing the crowd at the wetland

All participants received something to eat. There was a tent erected in case of bad weather. A DJ was in attendance, and the school kids were included.

Upland River Conservation was honoured to be included in the small organising committee, but the lions share of the organising was done by this young champion:

A crime

A recent foray into a project area revealed this site:

This is a drain, mechanically dug, to take roadside water accumulated in large puddles, away from the road. Where the crime comes in, is that the drain extends right across a functioning wetland, and into the stream beyond. Clearly the road contractor’s mandate was to get rid of the water by “fixing the drainage”, and that is what he did.

There is a common belief in this particular community (Ncibidawana) that all the fields and roads must be neatly drained to get rid of the water. It is a view we have heard expressed by traditional leaders, school headmasters, and local inhabitants. If only they knew the crime that this is!

There is such a burgeoning need for broad community education and consultation on these matters!

Regrassing

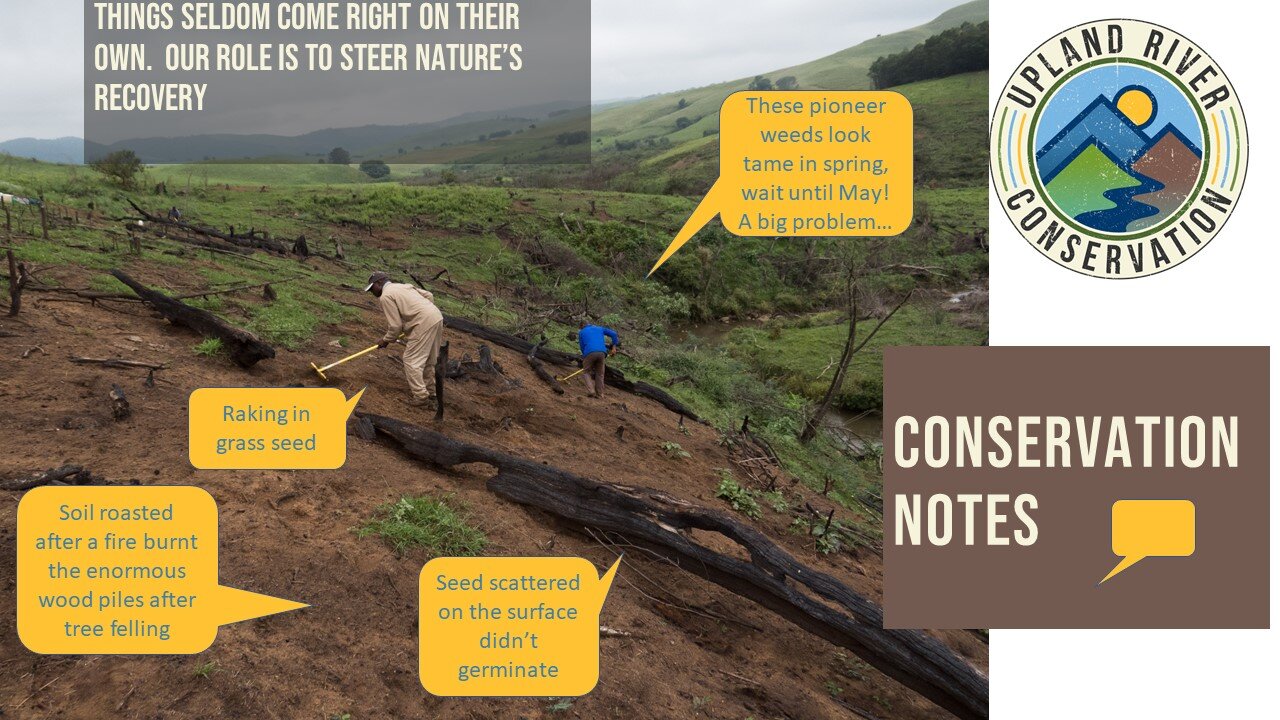

After a fire burnt the trash of a prior “working for water” project, the landowner found himself with a bare area due to the severity of the fire. Knowing that this area would be prone to infestation of invader species like bramble, bugweed and wattle, the owner was keen to get some grass cover in, to out compete the invasives. The value to him, was an extra hectare of grazing, so he called in Upland River Conservation.

With a small team, we got the area seeded in just two days. The seed was raked in, and all available wattle trash was laid along the contours to further prevent erosion. While we were there we sprayed brambles supplied by DEFF as part of their herbicide assistance program.

The work was further supported by a discount on the price, enabled by our small pool of donor money, so that the farmer didn’t have to pay an arm and a leg for this work.

The area was recorded by GPS, and before and after photos taken. A simple report was sent to the farmer once we were done.

A few weeks later we received a picture of the germinating seed, and a thank you from the landowner.

We hope to see more of this private/public partnered work, where government support, landowner contribution and donor resources come together to provide a cost effective solution.

And posted exactly 1 year later….take a look at how it came out!

Wash-aways averted

Thanks to the generosity of members of the public, landowners and interested companies, we raised the money we needed to make a start on the erosion control measures on the Poort Stream. The work was carried out by stalwart Alfred Zuma and his team, and with eco-logs sourced via DUCT from the department of Environment, Forestry and fisheries (DEFF).

The work was no walk in the park. The first 4 days were spent just carrying eco-logs the approx 2 kms from the road head to the site. Once they were there they were laid out, together with brush found on site, in a manner that would make them go as far as they could, and prevent wash-aways to the maximum. Then our grass seed mix was sown, and raked in.

A visit around Christmas revealed germination. Somewhat patchy germination, it is true, but germination nonetheless, and lots of un-germinated seed still evident on the ground which will surely still germinate.

It was pleasing to see how the eco logs and brush had arrested topsoil after some of the big storms we have had.

All in all, a good result, with washaways averted, and the Poort stream has been running clear on our subsequent visits.

Fundraiser for the Poort Plight

Details of how you can donate to stop a catastrophic erosion event on an uMngeni tributary

The combination of : previously felled alien trees; steep terrain; and a runaway fire that burnt very hot, have left a highly erodable zone, right next to a pristine stream in the upper catchment of the uMngeni River.

For details of the critical work that needs to be done during September/October 2020 on the Poort Stream to prevent an erosion catastophe, please see the “Plight of the Poort” post and video below.

Here is a quick map showing where the featured problem area is:

We have now done a budgeting and planning exercise.

To get in there and do the minimum of work over 2 to 3 weeks, we need to raise R60,000.

We will be extremely grateful for all and any amounts donated, no matter how small. We have landowners in the area, as well as one or two businesses interested, and if we can add a number of small donations to that, we should be able to pull this off. Nothing would make us happier.

If we were to raise more than R60,000, we could comfortably spend up to R200,000 on worthwhile and more thorough remediation work in this zone. We are therefore setting about a quick fundraiser, with the aim of securing R60,000 plus, and we will put whatever we get, to good use.

The project is being run by Upland River Conservation and the Duzi-Umngeni Conservation Trust (D.U.C.T.) in partnership. Donations should be made to DUCT .

DUCT’s bank account is with Nedbank Cascades (branch no 198 765), account number 114 259 3509. An alternative account number is 134 307 4320.

Deposits should carry the reference “POORT.your surname”.

DUCT can issue invoices, as well as section 18 (a) tax certificates on request (contact Gill Graaf at “finance@duct.org.za” )

If you require any more information at all to consider a donation, please call Andrew on 082 57 44 262, or mail andrew@fowlerconsult.com

Thank you for considering a donation to this worthy cause.

The Plight of the Poort

This little stream will probably receive dozens of tons of silt in the next 3 months if nothing is done……

This mini project is not yet funded. It is just a few weeks before we can expect some heavy rain, and we would like nothing better than to be able to get into this valley and get some eco-logs in place.

Take a look at this short video. If the initiative grabs you, and you would like to contribute to making it happen, drop us a message on the “Contact us” page…….

The Poort Stream

Exploring a little known stream that forms an important part of the uMngeni River source.

It seems that the exact source of the uMngeni River is not only a point of conjecture, but because it lies on private land, and out of sight of any road or resort, also an enigma.

The source is made up of a series of wetlands in an area labeled by Begg in his 1989 publication “The Wetlands of Natal”, as the “uMngeni Sponge”. The best known of these sponges is a RAMSAR site known as “uMngeni Vlei”, which is a protected area. However, anyone walking the reaches of the upper river, will find a strong tributary entering the main river a kilometre or two below where it descends off the escarpment at the farm “New Forest”.

In fact, the observant walker would probably notice that many times, that tributary is in fact larger and stronger in flow, than the so-called main river.

The confluence of the Poort Stream (left) and the uMngeni (right), at Umgeni Poort farm.

The Poort stream has its source in another wetland of the greater uMngeni Sponge, that being the Impendle Vlei. This vlei sits in a high rural basin, overlooked by the village of Kwanovuka, and falling under the jurisdiction of the Impendle municipality. This wetland has no legal protection. It is heavily grazed, but despite this, it is in good condition, and it is a beautiful place to visit.

From this 162ha wetland (which forms part of about 2,500 ha of the uMngeni catchment that falls into the Impendle municipal area), the water flows through a narrow “poort” and into further wetland and a man-made dam on Ivanhoe farm, where it is joined by other seeps and streams. “Working for wetlands” has done some recent wetland restoration work on Ivanhoe farm, and the owners and management are commendable custodians of this important area. This area is also very important wattled crane breeding and foraging ground.

At the base of this farmed area, on a farm called “The Fold”, the stream comes together into a pretty stream for just a few hundred yards, before it tumbles over a 60m high waterfall into a steep gorge below.

The Poort Stream just above the falls

The Poort falls, with Ivanhoe farm in the middle ground, and on the horizon, KwaNovuka village

In the gorge the stream runs through a tumble of boulders, with beautiful natural forest on its south-east facing slopes and open veld on the other side. There has been some invasion of wattle trees here, but thanks to the efforts of WWF and the landowner, this has been attended to, and with good fortune and a committed funder Upland River Conservation hopes to see to the ongoing maintenance work here.

A short distance further on, the stream becomes enclosed in alien trees, first as uncontrolled wooodlot, and then into a well managed commercial forestry area. We would love to be rid of the patch of woodlot, but it is steep difficult countryside…….maybe, just maybe, we will find a willing partner with the means to get this work started…

The stream emerges from the forestry area and trundles a few hundred yards through open grassland, where it then joins the uMngeni itself on Umgeni Poort Farm, where it flows at the toe of a beautiful natural forest.

Upland River Conservation’s projects that affect the Poort Stream are:

The Impendle Vlei inititiave (for the source)

Streamside restoration (for maintenance work in the steep gorge where WWF cleared)

uMngeni Co-Funded clearing (for that woodlot area that borders the commercial timber)

Visit the Projects page on this website to learn more about the above project proposals.

D.U.C.T. on the upper uMngeni

A short video, showcasing the work DUCT has done since the banks of the upper uMngeni where cleared of wattle in the Dargle above the Dargle falls.

The Duzi uMngeni Conservation Trust have done considerable work on the uMngeni in the Dargle valley in recent years. Andrew Fowler meets up with Alfred Zuma on site and we take a tour of some of the work being done there:

The Upper Elands River in KZN

Taking a look at the recently proclaimed nature reserve in the headwaters of the Elands River.

The very upper Elands River flows through a recently proclaimed Nature Reserve called Tillietudlem, in the KZN midlands. Tillietudlem have done fantastic environmental work.

We applaud them!

Read the full write up at:

http://enviroreport.org/?p=275

Replacing Indigenous Forest Patches in the Riparian Zone of the Upper uMngeni River

Re-establishing indigenous forest patches

“The promotion of indigenous deciduous trees for rehabilitation of clearing programmes may be important as there would be no transpiration during periods when water resources are limited”

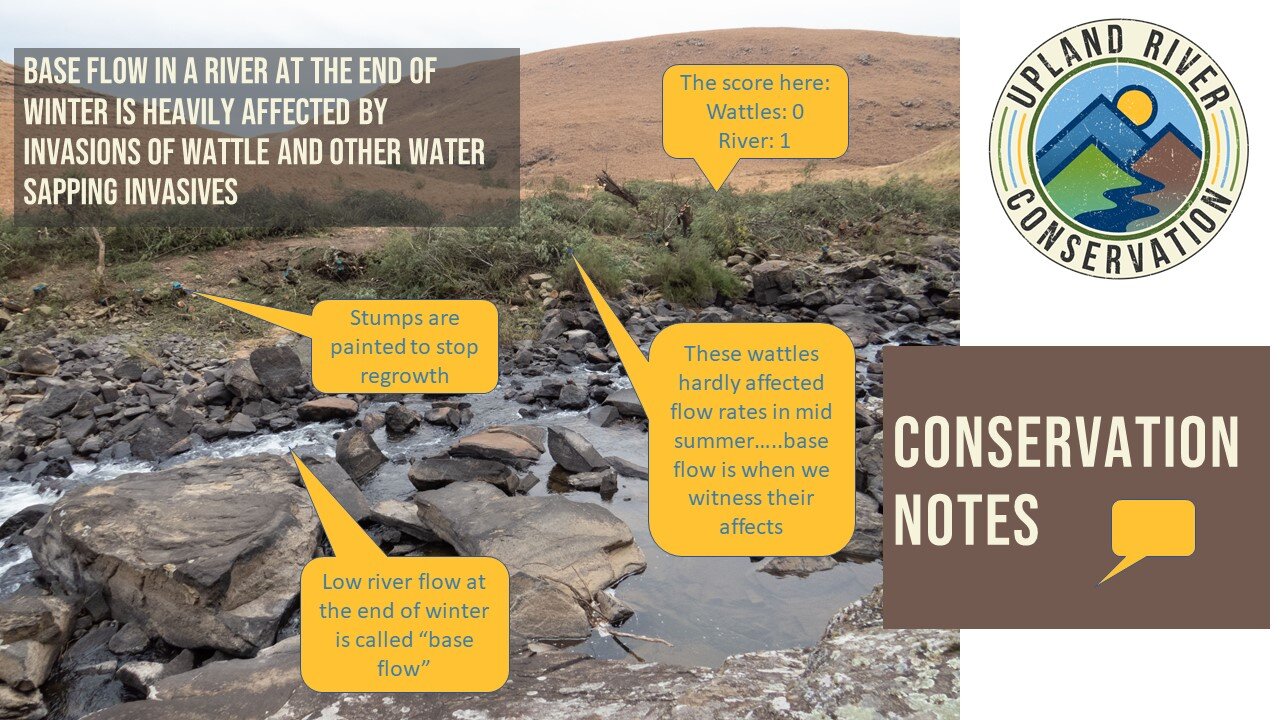

“The total accumulated sap flow per year for the three individual A. mearnsii and E. grandis trees was 6548 and 7405 La respectively. In contrast, the indigenous species averaged 2934L a, clearly demonstrating the higher water use of the introduced species”

The above statements are just two statements extracted from the publication mentioned above. While one has to be careful not to extract just the information that proves a pre-conceived notion, having read the paper, I think these take-outs are a fair representation of the whole, albeit overly summarised. The paper displays graphs in which is demonstrated how the alien (evergreen) species have a continual high water demand during the year, whereas the deciduous indigenous species, with their winter dormancy, show a very low water demand in the dry winter months. The dry winter months are those in which the river experiences its lowest, or ‘base’ flows, and is also the time of highest irrigation demand along the river.

This additional seasonal understanding of matters goes a long way to fully comprehend the extent of the demonstrated hydrological benefits outlined in the report. This also serves in justifying the expense and difficulty of removing alien invasive species in catchments generally, but more particularly along immediate riparian zones. The applicability of this report to the projects of Upland River Conservation is leveraged even further by the fact that this two year study was done in the heart of our Upper uMngeni Super Catchment project area, on New Forest Farm.

Before having been alerted to this study, we had identified seven small areas where alien invasive species have been removed, and where we hope to establish small indigenous forest patches. There are no doubt other suitable sites as well, but these are the first seven that have been mapped.

This was prompted by the notion that having removed the tree canopy from the river banks, we may have caused a sudden warming. While the river banks were largely unshaded a hundred years ago the more recent slow ingress of the alien canopy may have mitigated slight global warming. With the sudden removal we may have caused the environment to “catch up” on that warming in a short space of time. This has made us mindful of re-establishing tall woody river bank vegetation to achieve a natural level of shading. This shading would comprise mainly tall grassland and some Nchishi , but in at least in some places it means re-forestation with indigenous species.

The sites have been carefully chosen based on observation of where forest patches do occur, and where they might have occurred before the severe alien wattle infestation, which might have displaced them. In several cases, lone indigenous trees were found left standing after the wattle had been felled. In all cases the sites are steep, south-facing slopes along the river or tributary course. These areas are cool, and remain moist enough that they tend not to burn in winter.

In fact, money has already been raised to re-establish one of the seven envisaged forest patches.

With advise from a local indigenous tree nursery, and armed with a species list from another scientific study in the same forest, we plan to first establish the forest precursor shrubs. Once these get going, they are likely to form a frost- free micro-climate and canopy in which the trees themselves have a better chance of surviving the critical first few years. Once that is achieved, we plan to plant the trees themselves. These will of course include evergreen indigenous species, in the interests of maintaining the natural biodiverse mix, so the hydrological benefits may not be as stark as those reported in our opening quotes. The initiative does however represent a return to what conditions may have been before the invasion of alien trees.

In the interim, erosion control and re-grassing has been a priority for the bulk of the cleared river bank areas. Much has been achieved, but there remains a lot to do, especially along the banks of the Furth stream. Re-grassing efforts, and any required erosion control will continue parallel to our reforestation ambitions. We are currently exploring innovative funding solutions for each of the remaining six sites.

We certainly believe that the distinct and easily identifiable outcome of a forest patch, visible on Google Earth from anywhere in the world, might have appeal to funders who would like to be able to see the fruits of their contribution. Added to that, these small forest patches are between 800 and 5000 square metres only, and are therefore not expensive to create.

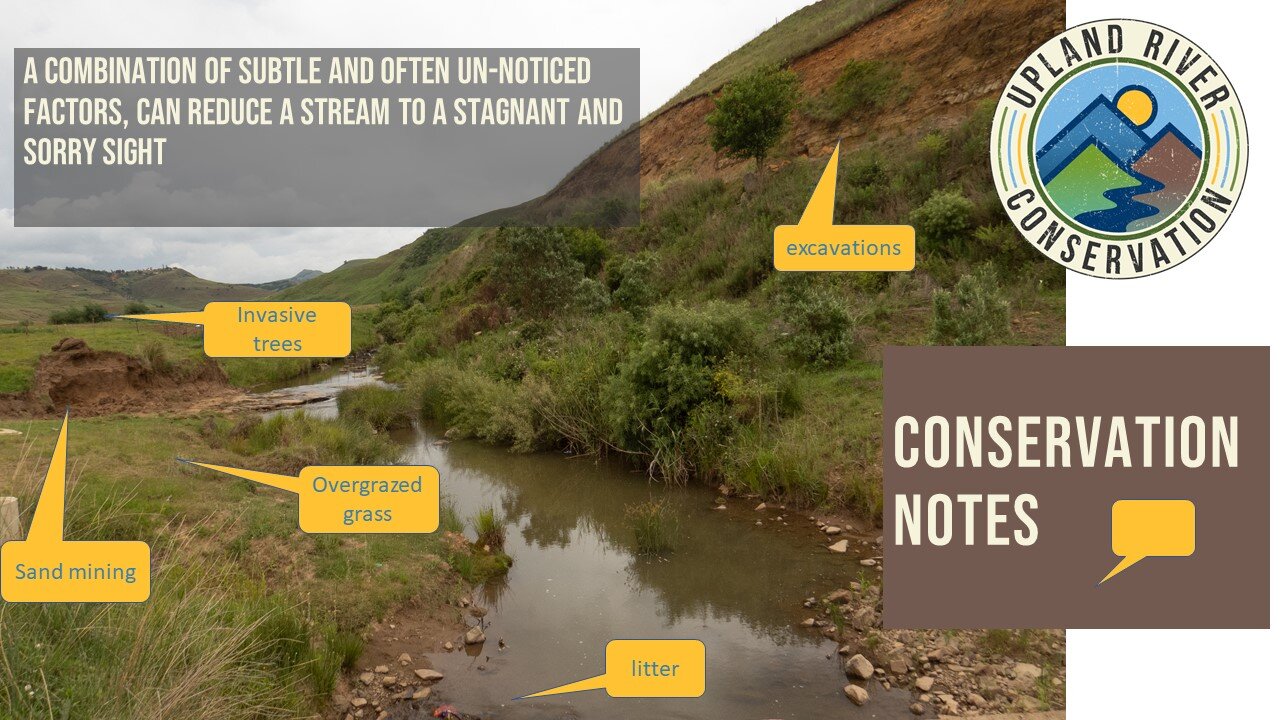

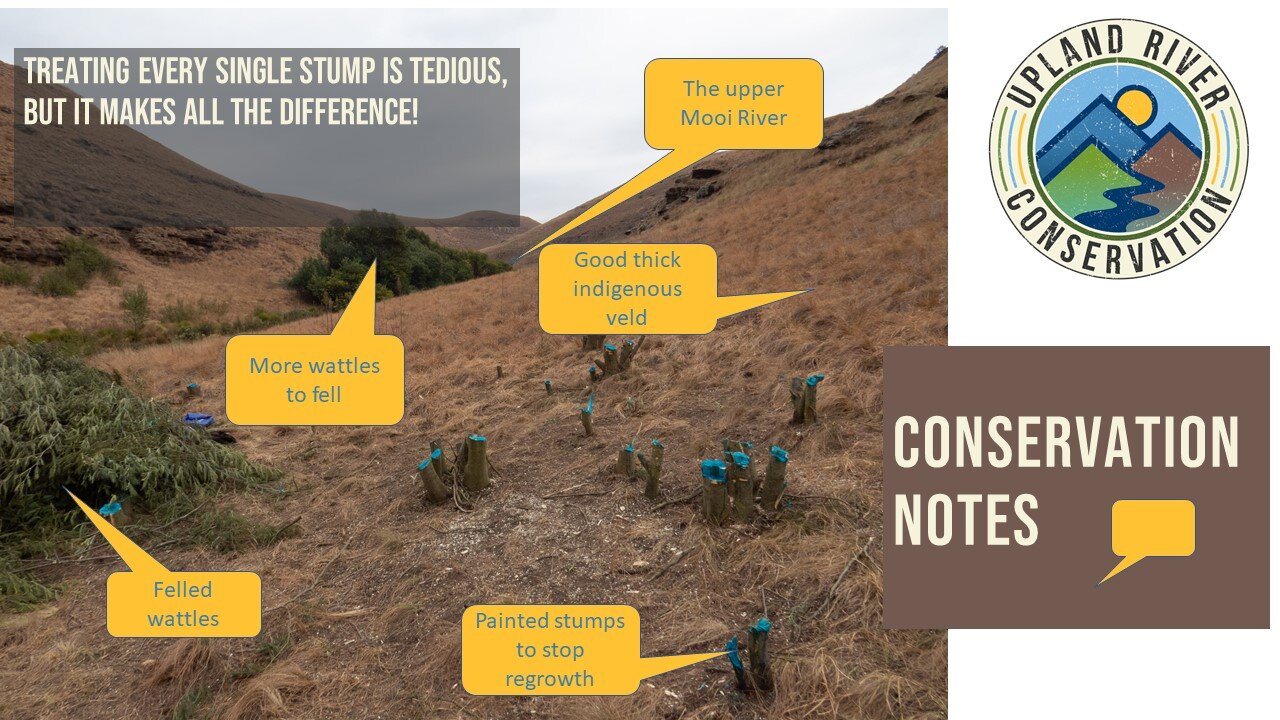

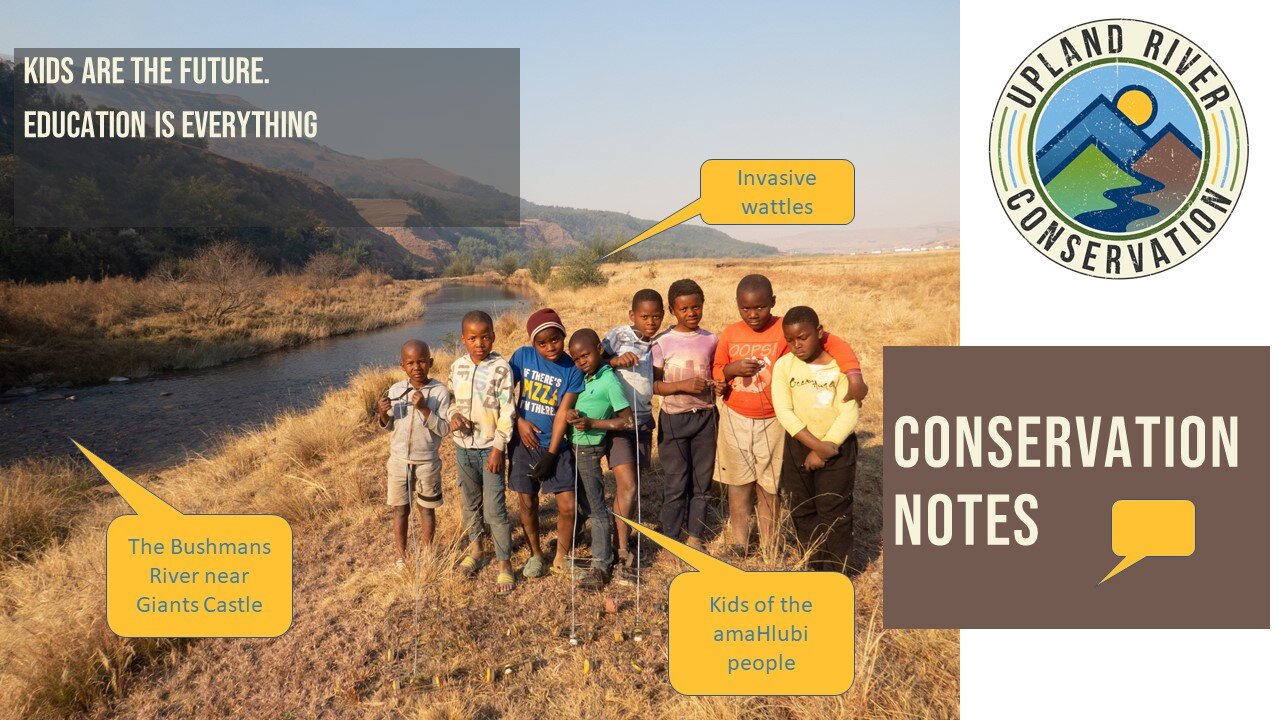

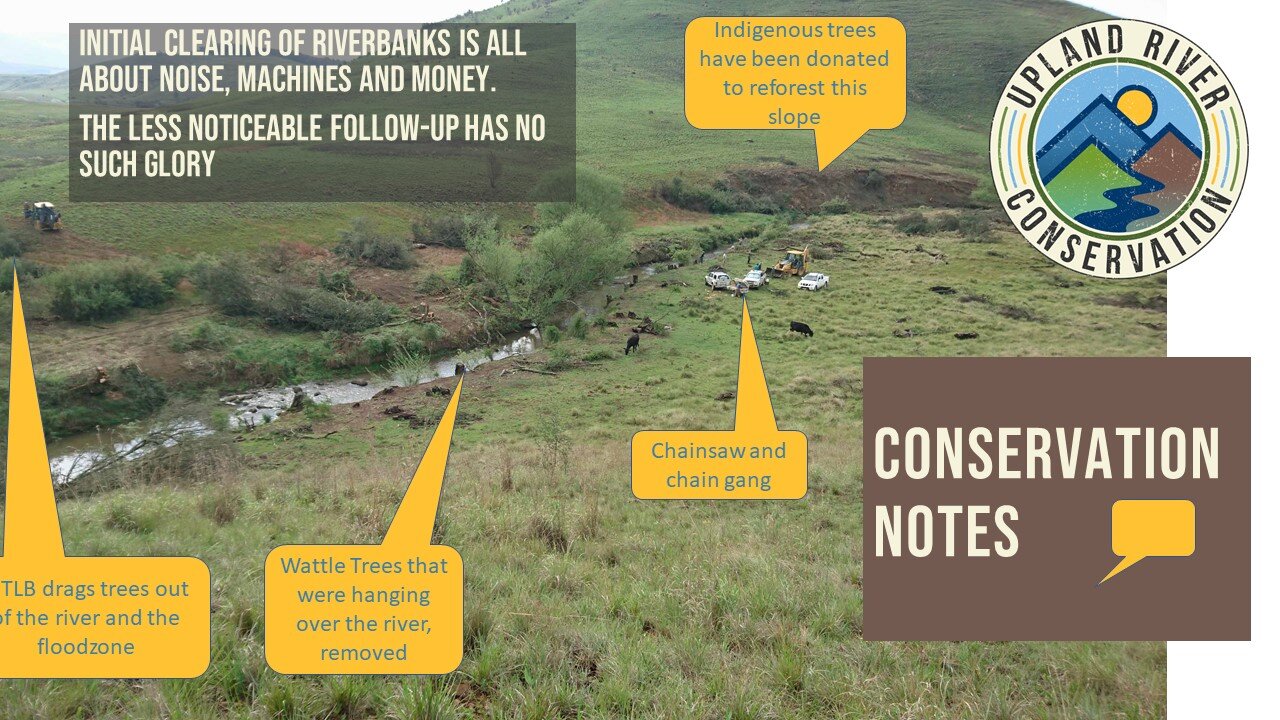

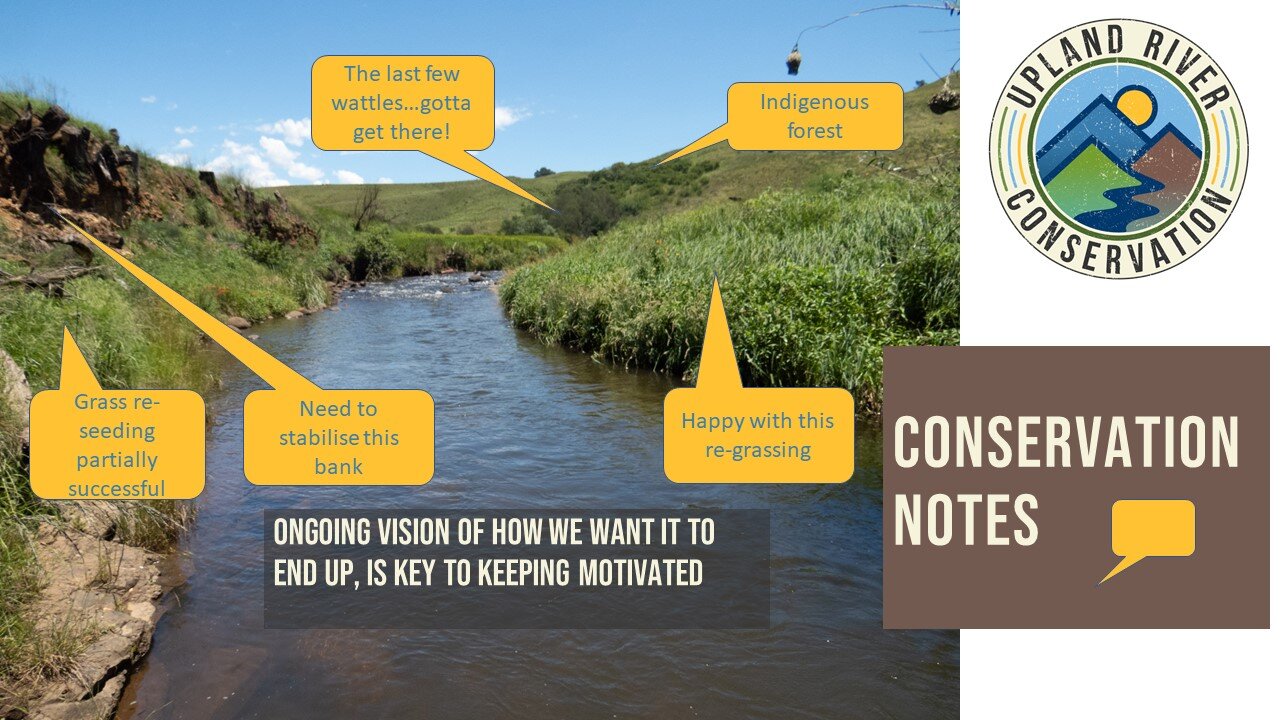

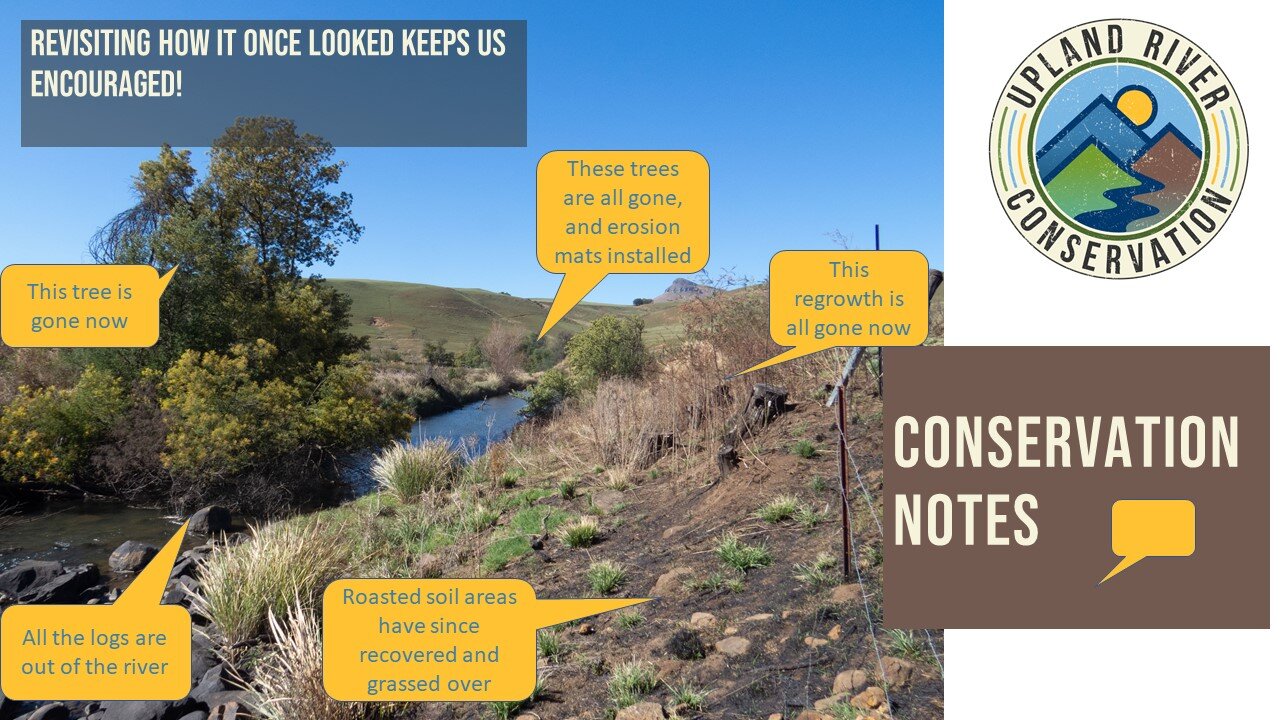

Conservation notes 1

A short slideshow giving you a glimpse of our successes, challenges and inspirations: a window on our world in the upland river catchments

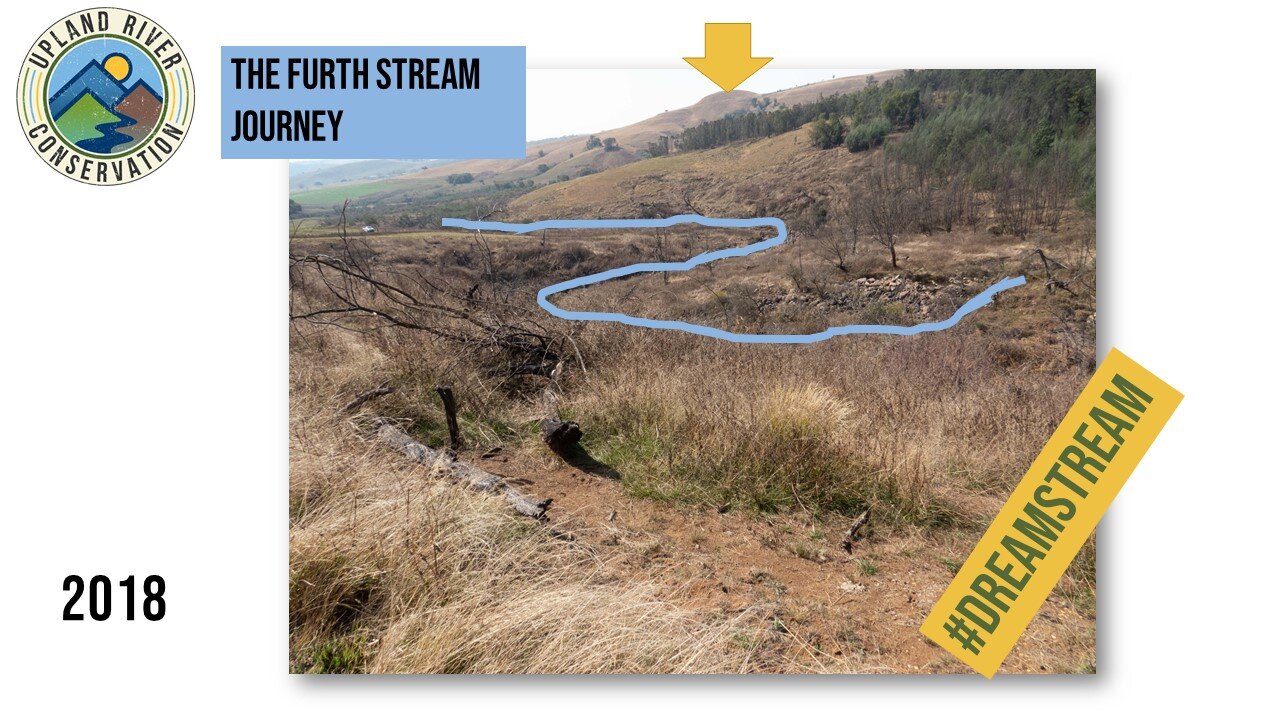

The Dreamstream

The Furth Stream is a good example of an area that was cleared of wattle, but which is in need of ongoing care and rehabilitation.

The Furth Stream is a tributary of the uMngeni River in the Dargle Valley in the KZN Midlands. This stream became inundated with black wattle trees in the approx last 5kms of its course, before its confluence with the uMngeni. Back in 2013/4, and stemming from a biodiversity stewardship program in the headwaters of the uMngeni, WWF arranged funding to clear the stream. That funding was part of an innovative Water Balance Program, in which industries downstream in the catchment were encouraged to become water neutral, by funding the removal of water-sapping trees in the catchment to the extent of their water use.

The stream was cleared of wattle initially, and then for 3 years thereafter, regrowth was controlled. After the 3 year period, the landowner is responsible for taking over the area, and keeping it clear of the invasive wattles.

In the case of the Furth Stream, the lower 4kms of the valley benefited from the input of the landowner’s lessor, namely the Natal Fly Fishers Club, who assisted the WWF in the day to day management of the contractor, and in the handover phase.

The devil lies in the detail of the hand-over to the landowner, and in the extent and nature of the follow-up measures required after the initial 4 year period. In several areas within the uMngeni catchment, the extent of the wattle regrowth, and the ability of grasslands to re-populate the cleared areas, have made for a successful formula.

The valley of the Furth stream is not one of them.

Here, difficult steep river valley territory has somehow contributed to rampant regrowth of wattle and other pioneer species. The amount of work required to control this, and to return the landscape to an economic grazing asset for the farmer, exceed the resources of the farmer, both in terms of cost, available time, and number of labourers to do the work.

Unlike some of the open hillsides that were cleared, the follow up work in the Furth Valley has been arduous. Between 2016 and 2019 the contractor passed through the valley twice each year, cutting and poisoning wattles and other plants. In 2019 the waste timber was removed from the immediate riparian zone, and in most years, fire passed through the valley. In witnessing this 3 year process, it was at times difficult to assess whether progress was in fact being made, or if the valley was going backwards.

In reviewing photographs and Google Earth images, it is clear that progress was in fact made, but even now, walking in the valley at times of rank re-growth, a layman would struggle to appreciate the amount of work that has been done, or to see the vision of what the valley should, and could ultimately look like.

In recent initiatives, post the handover to the landowner, minor (and sadly insufficient) clearing of regrowth has occurred, and erosion measures have been implemented by Upland River Conservation (URC) with help from the Duzi uMngeni Conservation Trust (DUCT) , The Natal Fly Fishers Club (NFFC) and the landowner. These measures have included planting of grass seed, and installation of erosion control mats, but are on a pilot scale only, due to the limit of resources.

At present the valley suffers from earth that was baked , and damaged, in fires that went through the valley and the piles of brush that lay there after the clearing work. The ground lies bare in many places, and in others is conducive to the germination of only wattle, bugweed, khakhi weed, bramble, and blackjacks. Grass cover of palatable species or otherwise, is currently very poor. The rank regrowth of combustible material, and the tendency of grass species to tolerate fire, act as incentives for the landowner to burn the area, and to the layman the burning practice achieves a “tidy up” which seems to have merit. However for a return to good basal cover, and soil structure, in which organic matter and mulch serve to speed the re-establishment of viable grassland, a more expensive management protocol is probably required.

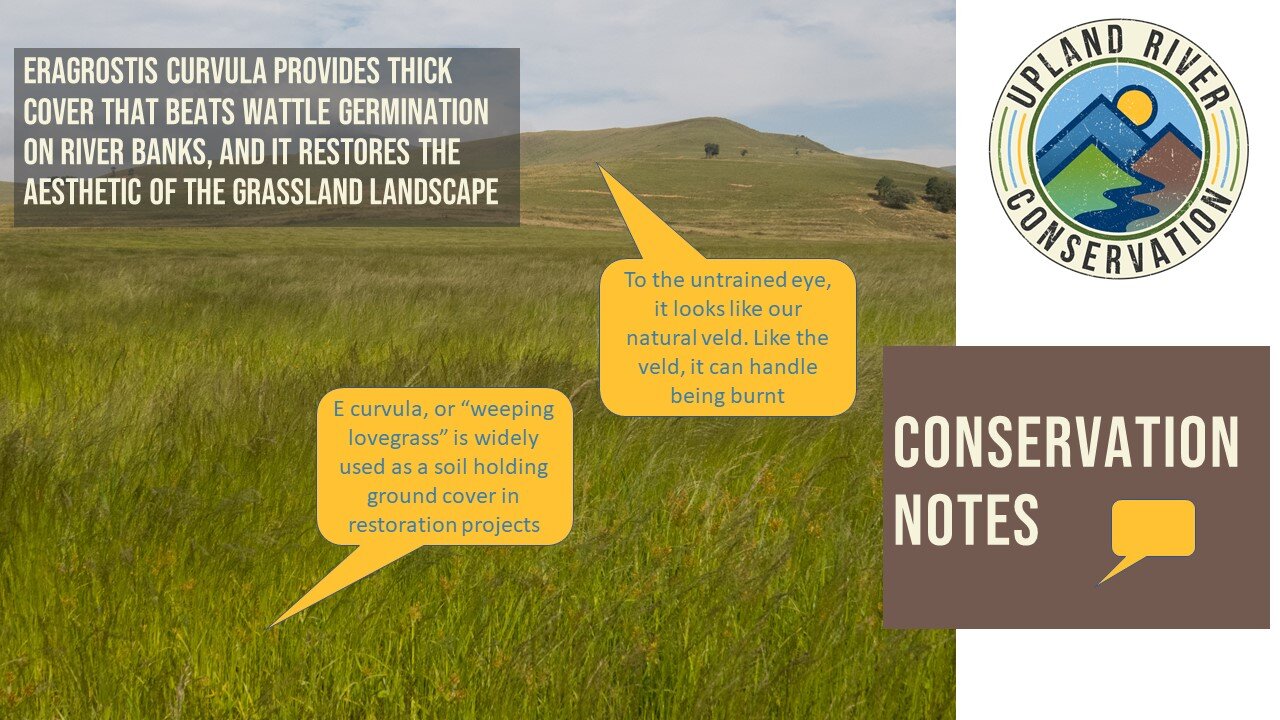

Our objective is to continue to fell regrowth of alien pioneer species during the summer, so that a fire hazard does not accumulate ahead of the dry winter months. At the same time we seek to sow grass seed, which will benefit from the mulch effect of the cut weeds. So far, in our pilot areas, we have used a mix of seeds which includes fast germinating eragrostis teff, together with slower germinating indigenous species. e teff is indigenous to Ethiopia, but is a non-viable annual grass, so its purpose is merely to secure the soil, and out-compete weed seeds in the first season, while the slower-germinating species take hold. Once the slower species do take hold, it is intended that they too will compete with weed seeds by creating a cover through which the weeds are less likely to grow. Weeds growing within viable grazing species will also be controlled by grazing cattle. Once this carpet of dense cover is established, fire will again be an important part of the restoration formula. In addition to the above, old logs and erosion control mats will be used to stop sheet erosion where it occurs. The above is the protocol being implemented in the pilot areas.

The end result which we hope for, is a densely grassed valley, which has economic value to the farmer as grazing, and in which normal, and affordable agricultural practices of fire and grazing are adequate in preventing significant re-infestation by alien invasive plant species. Early indications are that we may have achieved this, at least to some degree, in the pilot area.

The Furth Stream work falls within URC’s “Upper uMngeni Super Catchment Project” proposal, which is currently seeking funding. In the meantime URC and the landowner will continue with what pilot work we are able to afford.

The tipping point

Exploring what turns an unrealistic environmental dream into a financially viable project, ready for execution on the ground.

At a recent meeting of sugar cane industry players, we learnt how bio-control can be an effective and very cost effective strategy to counter eldana worm. It also became apparent, however, that to convert to biological methods, one has to stop the traditional chemical solution, and then wait until the population of “good bugs” recovers from all the years of spraying, before they can be effective.

It’s that “wait” that’s the problem!

During the wait, the pests could wipe out a crop, or diminish income to the point where the farmer won’t survive the change-over. What businessman would take that risk!

This seems to be a common thread. There is a cost or a risk to converting to more environmentally friendly practices that simply isn’t worth it to the individual farmer, or community who would have to bear that cost or risk.

But what if the beneficiaries of the environmental gains, were to partially back the farmer, or share the risk, in return for the gain that they (and often the farmer) are after?

Let me give you a practical example of a beef farmer on the highland sourveld of KZN. He has a veld farm, and on it he has groves of wattle trees that were there before he was born. If he felled them and converted that land back to veld, he would gain, lets say 60 ha of grazing. But the felling, erosion control, replacement of the woodlot (with one of a more desirable tree species…for storm cover for cattle) , grass planting and five to ten years of weed control, will cost him about R10,000 per hectare.

A farmer recently told me that he had done the sums, and that in the lifetime of him and his son, they will never generate enough beef farming income to cover that. Sixty hectares at R10,000 per hectare: that’s a R600,000 loan from the bank, plus interest. And what NGO would invest R600,000 on a private farm for extra water, the extent of which can’t immediately be measured? The result is that nothing gets done, and the wattle groves stay there. The farmer still wants to get rid of them, and the city below still wants more water, but a generation goes by, wattle seed keeps spreading, and nothing changes.

Maybe we need a catalyst who asks:

How much would company X invest in creating employment opportunities for its CSI score?

How much would municipality Y invest to generate more water to fill the municipal dam?

Is there a risk that can be insured?

How much would the farmer invest to get that land back into beef production?

How much would the local farm-stay put in, to be able to market their venue as part of an environmental project?

How much would the seed company put in as part of an advertisement for their grass seed?

The chances are, that if each of the entities in the above example stretched their budget, right to the brink of what they are comfortable with, and if there was a protagonist with enough passion to get them to the point where they all said “OK, let’s do this!” , that might just be the tipping point that gets the job done and changes the landscape for the better, forever.

At Upland River Conservation we are always searching for the environmental wins that will benefit a catchment (Examples: fencing off river banks, protecting springs, putting in contour belts, planting row crops further from the stream, blocking drains that dried up wet areas, managing for better veld condition……)

We are also thinking about what the costs and risks would be to achieve those wins.

Then we consider who would gain from the work, and in what ways, and how much investment might it justify from them.

We believe that society cannot expect the landowner (farmer or rural community alike) to shoulder the burden of this work. We are passionate about getting the work done. We are looking at building project concepts that reach the tipping point. Call us the passionate protagonist.